Is your sample as clear as you think it is?

With this very simple illustration, we show that “clear” to the eye is not necessary “clear.” You can easily do this test, too. The picture on the left is filtered tap water with a laser pointer shining through. Notice how the beam on the far-side of the beaker remains pretty focused, even with the very long pathlength it travels and the poor quality of the glass beaker. Perhaps most importantly, notice how we cannot see the light in the water.

Compare this sample with our ‘experimental’ sample: Flat Coors Light. As the laser shoots through the beer, it is visible, just as it would be in a smoky room. Yet, the turbidity of this beer sample is not noticeable to the eye.

In addition, notice the breadth of the light on the forward- and far-side of the beaker. This is “scatter.” These are all the photons which miss the detector. This is the reason your cuvette spectrophotometer cannot get the right answer in the face of any turbidity in a sample. This is why you need a CLARiTY.

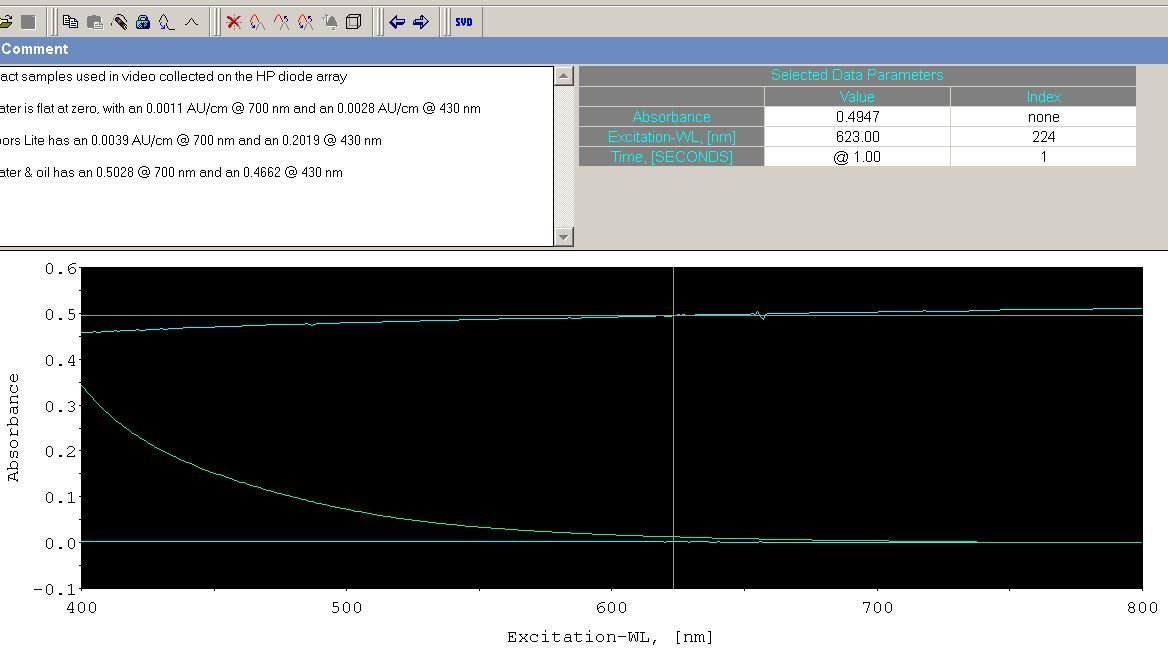

The attached Water & Coors Plotted:

These scans were collected on a very good quality UV/Vis spectrophotometer in a cuvette. The filtered water has a 0.0011 AU/cm @ 700 nm and 0.0028 abs/ cm at 430 nm. The beer’s 700 nm reading is 0.0039 AU/cm and the absorbance towards the UV has the exponential rise that one sees in all light scattering samples; absorbance/cm at 430 nm is returned as 0.2019.

Even a ‘clear-to-the-naked-eye” sample as too turbid for a correct measurement.

The “scatter” results in an apparent high absorbance from all cuvette spectrophotometers.

The more turbidity – especially in the UV – the more essential a CLARiTY becomes for collecting the correct answer.

Water & Coors Light plotted

This video shows the difference in turbidity between clear water, soapy water, and Coors Light beer. Even "clear" liquids have turbidity that affect the accuracy of results you get from a cuvette spectrophotometer.